One long-time frustration of mine is how people like to lump climate change in with deep-green ‘environmental’ issues. From deforestation to anti-GMO and protecting polar bears, climate change often gets thrown into the broad tranche of politicised issues that are not systemic to the financial system.

Our entire society and global economy was built around a stable climate. As such, any changes in the climate system fundamentally impact individuals, families, businesses, cities, and nations. This means that the impacts of climate change are not about far-away polar bears, they are fundamentally part of the global financial system.

Fortunately, the zeitgeist that climate change as a financial issue has shifted. Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England and Chairman of the Financial Stability Board, gave his now-famous 2015 speech ‘The Tragedy of the Horizon’ suggesting climate change could cause the next financial crisis.

Since then, it’s clear that key players from central banks to large institutional investors have begun attempting to integrate carbon risks into their decision-making given the seismic reallocation of capital taking place.

However, they remain hamstrung by traditional metrics. Thanks to simplistic carbon-footprinting measures, carbon risk has traditionally been diluted with the broad scope of ‘Sustainable Investment’ and the qualitative non-financial metrics that come with it. That’s a problem for all investors.

In this month’s Carbon Alpha newsletter, I explore trends in Sustainable Investing, the utility of ESG scores to assess carbon risk, and some ways to better integrate carbon risk into financial decision-making.

The evolution of ESG: sustaina-bubble?

Companies operate to create value for society. With that comes a social license that continuously evolves. As social progress is made in areas from human rights to gender diversity, companies must evolve too, integrating these new social norms into how they operate.

If a company is exploiting child labor, then it rightfully doesn’t have a social license to operate. It’s obviously not a great investment either, no matter what your opinion of child labour is.

A myriad of metrics have been formulated by ratings agencies over the past two decades to assess companies’ performance across this broad range of evolving environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) issues. In fact, over 50 ESG metrics can now be assessed, with this number growing.

Companies can be now be rated on things like anti-competitive behavior, human rights, workplace safety, gender diversity, water, biodiversity or recycling. These give us diverse insights across important issues - but a challenge often associated with them, is how much can we trust them and how can we use them?

Sustainable Investing, sometimes called socially responsible investing or ESG investing, use these ESG metrics to rate stocks, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), and investment funds, as a proxy for sustainable investing.

There has been a surge in ESG investing - with COVID-19 only fuelling the market. By some estimates, some $35.3 trillion - or ~36% of total assets under management - are now ‘sustainable investments’.

Scrutiny is increasing on ESG investing. The EU this month cracked down on ESG fund greenwashing, causing a $2 trillion fall in on-paper assets that can call themselves “sustainable”. Aside from the debate on whether the ESG-bubble has arrived, the question I want to explore is whether ESG metrics are helpful for investors on climate and carbon?

Carbon risk is not binary

Traditionally, ESG metrics have been used for screening purposes (either negative or positive) for investment decisions. Certain sectors, companies, countries and activities can be easily screened by activity as measured by ESG metrics (e.g. weapons, tobacco, coal) or via norm-based standards (e.g. human rights, labor rights).

ESG-based screening has also been used for fossil-fuel divestment (eg any coal, gas or oil activities), which has gotten alot of media attention over the past few years. But for carbon risk, ESG-screening doesn’t work as it takes a sledgehammer to a very complex problem.

Unlike activity-based ESG screening (eg child labor or thermal coal), carbon transition risk is not a binary equation. Carbon emissions don’t need to be 0 tomorrow or even in the next 10 years - it’s a carbon transition. Over-reliance on metrics that don’t account for future transition risk is a problem. Not all metrics are created equal and we need deeper insights to allow us to take well-considered action and ensure we are not destroying (rather than creating) value in the process.

Over the transition period, a company can still emit carbon emissions so long as they are generating the requisite value. As the transition to net zero continues, a company should only be emitting carbon emissions if the marginal benefit of the carbon emissions is greater than the marginal cost. That means coal and oil will still play an important role in the shorter term and basing it on simplistic carbon footprinting ESG metrics is not helpful for investors.

Qualitative, Non-Financial ESG metrics can hide carbon risk

Climate change and carbon metrics are included in the suite of ~50 ESG metrics from rating agencies. Typically, a company is scored based on a much broader mixture of sustainability indicators. Alot of these are qualitative judgments on how strong governance structures are or whether a company has issued an aspirational target for net-zero. Some companies get good ESG sustainability ratings as a result - whereas the real carbon risk is buried. Here’s an example…

Example: Carbon risk for major Sustainability Index

To help you understand how good ESG ratings can hide real carbon risk - I took a portfolio of the top 10 securities from one of the largest Sustainability indices in Australia. I then built an equally-weighted portfolio of those top-rated ESG Sustainability companies and uploaded the portfolio to Emmi to better understand the carbon risk. Here are the results.

Top 10 Listed Australian Securities in a large Sustainability Index:

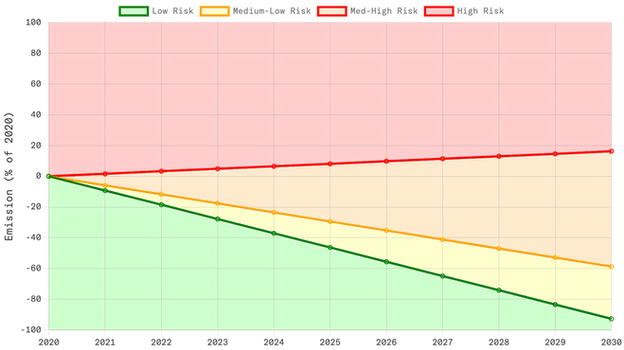

Emission reductions needed to maintain carbon financial risk bands:

What we found was no clear correlation between those companies that rated highly in ESG-investing via a top Sustainability Fund and carbon risk metrics via Emmi. On average there is a medium level of carbon risk while only 2 out 10 companies listed are currently net-zero aligned based on their existing carbon finances.

Idiosyncratic vs Systemic Risk

The other problem with lumping climate & carbon in with the 50 other ESG issues is that climate change is fundamentally different to other ESG issues. It presents a systemic risk to the financial system as highlighted by Mark Carney, while other ESG issues have idiosyncratic risk. Systemic risk is the likelihood of damage being done to the health of the system as a whole. Idiosyncratic risk, by contrast, is the likelihood of damage being done to one or small-selection of securities.

By including climate within the scope of ‘Sustainable Investing’, traditional ESG downweights and keeps climate change external to integrating with investment decision-making. As a result, hidden risks remain throughout the system. This is why we hear talk of ‘Green swans’.

It’s easy to see why this has occurred given ESG carbon metrics are based on carbon footprinting and qualitative analyst judgments. How can investors convert a companies carbon footprinting or carbon intensity rankings into risk or pricing?

Traditional ESG metrics work entirely in a financial vacuum, scoring carbon emissions. But the fundamental question for investors is how best to re-position capital markets to prosper from the low carbon transition.

Traditional carbon footprinting ESG metrics haven’t been built to integrate into financial decision-making. Ultimately they can only be used for screening or more likely, sales and marketing departments.

Integrating carbon with finance unlocks opportunities

Whilst ESG metrics have their place in decision making, traditional ESG-investing doesn’t solve for carbon risk. We need a new approach for carbon risk, an integrated quantitative financial approach to help investors make decisions that maximise alpha opportunities. The ultimate goal is to find the lowest-cost carbon pathway and there are many alpha opportunities in all sectors that ESG screening isn’t built for.

Source: Global Sustainable Investment Review, 2020

That is why over the past five years, institutional investors have started to shift their approach. A surge towards ESG integration has occurred (see plot above) while ESG screening as a strategy has declined, according to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance.

Yet traditional ESG metrics are incapable of providing a solution for investors that can solve for and easily integrate carbon into their financial decision-making. That is the reason we built Emmi. By providing quantitative risk management tools for companies and investors our mission is to re-position capital markets to prosper from the transition to net-zero emissions.

Using Emmi's flagship carbon metrics (emissions reduction requirements for scenario alignment, and Potential Capital Loss), we can help you to understand whether a company has the ability to thrive in a carbon-constrained world. Moreover, we can you to figure out whether what companies say they'll do will make a difference in terms of their impact on the world, or the changing world's impact on them.

Our approach is to focus on quantitative, objective carbon financial data today - then track that over time. As the carbon constraint enters the marketplace, it should be directly quantified and tracked as carbon risk over time, without qualitative judgments. Whether a company is transitioning towards lower carbon risk is demonstrated by data - not by press release.

Emmi does this by integrating 12 financial factors to understand the complete financial risk for investors. Each business unit (profits, dividends, revenue, debt, liquidity) is carbon benchmarked to give a complete risk profile of a company to the carbon transition.

By combining climate benchmarks with financial metrics, optimal carbon pathways can be projected for companies and their portfolios. This allows investors and companies to fundamentally benchmark carbon risk and invest in different strategies to ensure long-term alpha while demonstrating impact.

I hope you found this post useful. Next newsletter I want to go a bit deeper into optimizing carbon pathways to prosper from the transition to net-zero emissions.

Stay safe and well,

Ben